May 12, 2009

ORLANDO, FLORIDA – Matthew Ranfone was only two years old when he slipped out of his Orlando home, into an enclosed patio area and through a pool fence into the backyard pool. His parents found him minutes later floating face down. Matthew died 13 days later from the injuries sustained in the near drowning.

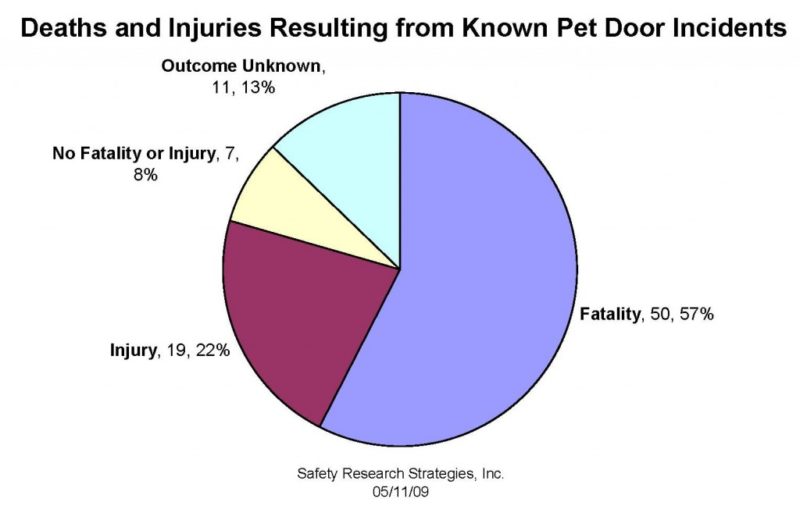

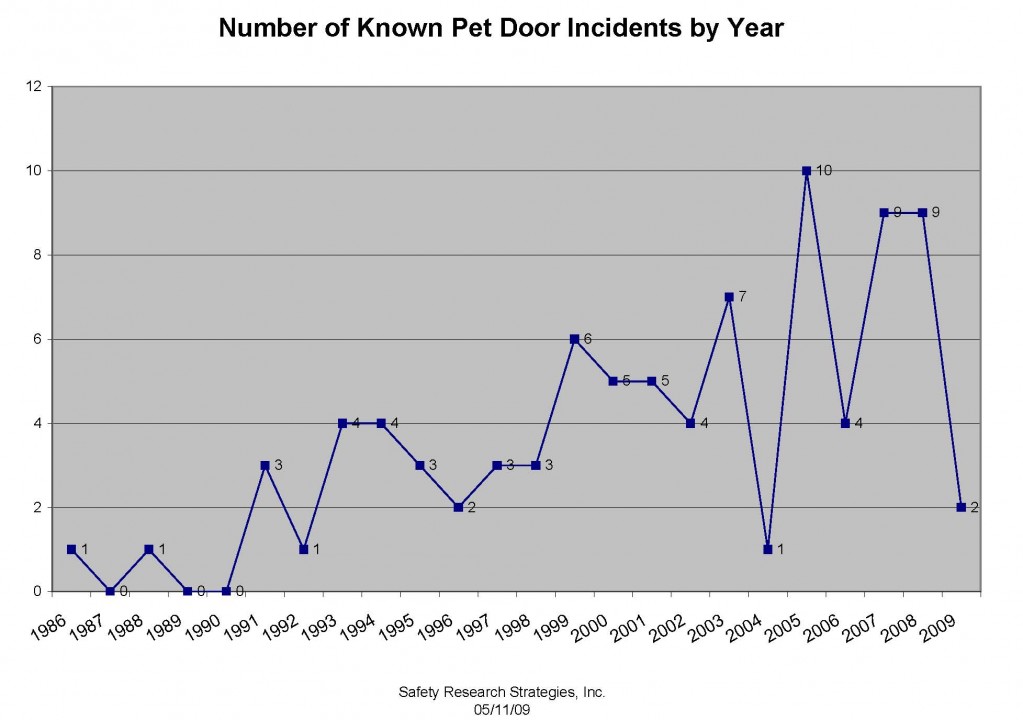

It’s a scenario well-known to a handful of child injury specialists – especially those who study the morbidity data in warm weather states. In fact, since 1996 there are nearly 100 documented cases of children endangered after exiting the home via a pet door. Nearly three-quarters resulted in injury or death. Mathew’s mother, Carol Ranfone, had no idea at the time that her son could easily escape through the small opening, but she is determined to warn other parents.

The map below identifies the location of the known pet door incidents. Red represents fatal incidents, blue non-fatal or unknown outcomes.

View Pet Door Incidents in a larger map

This week, the Ranfone family launched a website, www.PetAccessDangers.org, to raise awareness of this danger and advocate for change in the industry.

“Our family had chosen to respond to Matthew’s death by informing the public and working to ensure that pet doors are made safer,” Carol Ranfone said. “Matthew didn’t have a chance to grow up, but we hope that our advocacy will keep other children out of harm’s way.”

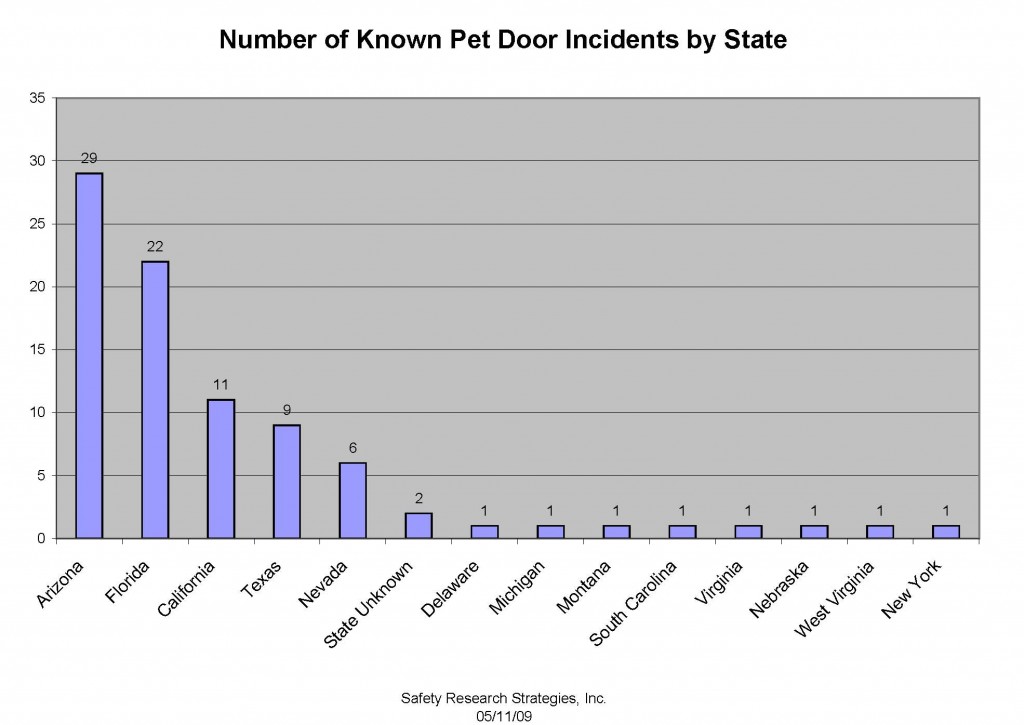

Dr. Timothy Flood, medical director of the Arizona Department of Health’s Bureau of Health Statistics has compiled the largest statewide databank of fatal and non-fatal drowning incidents. His staff has been tracking drowning incidents in which a pet door was factor for more than 15 years. Arizona, where backyard pools are common, has seen a steady stream of such incidents.

One recent example involved a child, nearly three years old, who crawled out of a pet door and fell into his family’s backyard pool in Auwatuakee, Arizona. His mother found him at the bottom of the pool. His eight-year-old sister jumped in to save him, but he died from drowning in the April 2008 incident.

“It’s a nationwide problem,” says Flood. “And it’s typical of sunny-weather states. We’ve had 26 incidents since 1993, at the rate of about one or two a year. It’s a real issue.”

The full scope of this problem, however, is unknown. Sources of childhood injury and death data – state medical examiners offices, coroners, the U.S. Product Safety Commission’s surveillance systems, hospital emergency medicine centers – often do not document egress when an incident occurs outside the home. Instead, their reports focus solely on cause of death or the nature of the injury. A few counties in California – Riverside and San Bernadino – and Maricopa County in Arizona are tracking egress data by using a Submersion Incident Reporting Form or similar form that was created by the staff of the Loma Linda University Medical Center. There is no centralized or nationally accessible data source that tracks drowning and near drowning events by point of egress or method of access.

Safety Research & Strategies compiled its data from the U.S. CPSC, media reports, medical examiners offices, child death review publications, criminal court neglect and abuse cases, injury prevention specialists, state health departments and the National Drowning Prevention Alliance.

“Based on our contacts with public health officials and child injury specialists, we know the problem is more widespread than our data suggest,” says Sean Kane, SRS president. “There have been individual researchers looking at local or regional data, but nobody has put it all together on a national basis. There are real obstacles to getting a clear picture – not only because reports don’t mention the point of egress from the home. There are also privacy issues that tend to obscure an accurate count.”

While a handful of child injury researchers are aware of the link between pet doors and childhood injury and death, even fewer parents are aware of the dangers posed by them. The size of the opening appears deceptively small. Parents may believe that their child is safely contained inside the home. But an average medium pet door with a typical opening of 8 x 11 inches is recommended by manufacturers for use with pets up to 40 pounds. A 95th percentile, three-year-old male child weighs only 38 pounds and can easily pass through this opening.

Through www.PetAccessDangers.org, Carol Ranfone hopes to spare other families from the pain her family has endured, and encourage the pet door industry to improve their designs. The website also urges public agencies, hospitals and medical examiners’ offices to incorporate a coding system to provide more accurate data as to how a child may have reached the water or other hazard. This information is critical to understanding the true scope of the safety issues surrounding pet door products and the risk they pose to the public.

Safety advocates and injury prevention experts are mulling a variety of next steps to address the problem. Kane says that a multi-faceted solution is needed that includes better data collection, improving secondary pool barrier requirements, prominent warnings from manufacturers and improved dog door designs, such as those that use radio frequency technology to lock the door, except when the pet wants to enter or exit.

Flood says that better data is key to developing appropriate solutions.

“Looking at age group of the victims is critical. It’s the toddlers – one to two years – this is an extremely targetable group and it’s going to help your marketing a safety message to an audience of young parents.”

Others are looking to the pet door industry for a better-designed product. Reasonable and economically feasible alternatives to the simple flap-style pet door closure exist, yet many companies are still marketing and selling these doors with no locking mechanism and without warnings. On May 23, 2008, the Ranfone family filed a wrongful death civil lawsuit against Radio Systems Corporation, one of the largest manufacturers of pet doors, marketed under the brand-name PetSafe. Depositions taken in the case revealed that senior officials understood that children could get through their pet doors. In fact, one of their product lines, Staywell, markets some of its products thus: “The dog door locks in both directions preventing young children from leaving the home.” They also admitted they knew of two incidents, going back to 2003, in which a child drowned after escaping through one of their products. They also conceded that it was possible to warn consumers about the possibility of small children using the pet doors, without any significant cost to the company. In fact, the company’s Director of Quality Steven Ogden testified: “I think all manufacturers should warn of hazards that their product can cause regardless of the age that it could cause them to, but certainly if it’s children or any age — any age of people.”

Nonetheless, David Anderson, director of the company’s pet access strategic business unit, said that the company wouldn’t consider adding a warning until the lawsuit concluded.

“Manufacturers, while quick to blame parents for a lack of supervision, are aware of the risk that pet doors pose to small children,” said product safety attorney Henry Didier, who represents the Ranfone family. “These manufacturers are in a position to reduce or eliminate the risk before the consumer even purchases the product, and to date, they have not.”

In the meantime, drowning prevention advocates are considering other preventative measures. In March, the Southern Nevada Health District proposed legislation that included language requiring that all pools be enclosed in a barrier or equipped with an alarm, but the legislation was not adopted.

“The pet door access is part of the puzzle,” said Kristin Goffman, executive director for the National Drowning Prevention Alliance. “It’s a weakness in the layers of protection that has to be addressed. We find that in some cases, people have forgotten the pet door even existed. It was disregarded as a risk.”

The National Drowning Prevention Alliance believes that the best measure would be a requirement that all pools are enclosed in an isolation fence, so that unnoticed points of entry, such as pet doors, are not a factor. Maureen Williams, NDPA founder and communications manager for D& D Technologies, the maker of MagnaLatch, a magnetic pool gate latch, said that her company has known about the problems with pet doors for years and has often included a reminder in its yearly press release. Warnings, however, are inadequate, she said.

“It’s a good idea, but warnings do more to protect the manufacturer from liability rather than to prevent the incident,” she said.

But the NDPA agrees that thorough research into the problem should precede any solution. It is currently conducting its own research into parents’ information and attitudes about children’s swim lessons. NDPA members are also participating in another project in conjunction with the California chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics to develop a handbook on drowning data collection.

“I don’t think there will be any change in policy and messaging until we’ve done the research, Goffman said. “A second critical component of moving drowning prevention forward as these new issues are clarified are the engineers – who will take the ideas out there and bring fabulous new products into the marketplace. But the first step is research.”

Consumer Alert: Children’s Deaths Tied to Pet Doors

ABC News – USA

The PetSafe door in the Ranfone home contained no warning to parents of the possible danger on its package or product instructions. …

How little kids can escape through pet doors Consumer Reports